Over the past two weeks, I worked as an intern volunteer at the University of Edinburgh Archives, where I catalogued the collection of Marjorie Rackstraw. When I arrived, there were four boxes that were reasonably sorted by topic, though many folders full of unsorted correspondence, still in original envelopes. With the expert advice of cataloguing archivist Aline Brodin and other kind coworkers in the CRC, I methodically worked through each box, and after understanding the themes of the collection, Aline and I found an arrangement of subfonds and series that suited the collection best. I began cataloguing, and rehoused documents as I came across them, removing pins, and staples that were nearly 100 years old. I was often moved to tears by the letters I read in Marjorie’s hand, and was soon hooked to the story of her life that lay in these boxes, and the care she took in saving each document. As time went on, it became more and more difficult to read the letters only with an eye for cataloguing, and the pull to immerse myself in the story buried in the physical evidence became stronger than ever. Occasionally I would succumb and read an entire series of letters, and these times brought the perspective of other series into clarity, as well as aided me in crafting her biography.

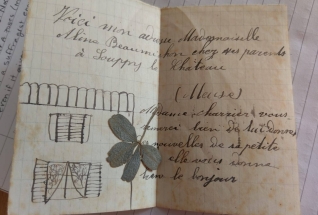

Marjorie Rackstraw was born in 1888, the second of five daughters, and her primary years were spent in an infirmary for children, where she was treated for serious spinal trouble (possibly undiagnosed polio). Throughout her life, her sharp features and unusual frame were marked upon, but her laugh and infectious care for others were  often stronger impressions. She spent a year in Paris, France before University, and the collection contains many letters from her mother and father back in England during that time. Her father was a successful businessman, owning several department stores. She attended Birmingham University, where she stayed in University House, a hostel for female students of the University. Here she met Margery Fry and Rose Sidgwick, who were to be sincere friends of hers, and prominent figures in her collection. Though both wardens of the University House, and a good deal older than Marjorie Rackstraw, they shared political interests, and it is easy to assume from their letters that Marjorie gained a passion for volunteer work abroad from Margery Fry. After University, she worked at Moray House at the University of Edinburgh as a Warden spent a year at Bryn Mawr University in Pennsylvania, USA, before taking an appointment in Buzuluk, Russia during the Great Famine of 1921-1923. She worked for a government administration tasked with distributing rations to starving people, and the collection includes over 30 detailed letters and reports she sent her family and Margery Fry during this period. I made the time to read these letters in detail, and it offered a useful perspective to view the rest of her collection, and where her passion for relief started. Most letters are, first and foremost, heartbreaking at their core. Rackstraw presents the facts, her observations, but even from the level headed writing of this down to earth woman, there is no escaping that she watched 1/3 of her village die from lack of food between 1921 and 1922. The springtime was always joyful, and the winters exceedingly difficult. Every accomplishment was met with a complication from the weather, which prevented new plans from going through. This was an effort of survival against the elements, in an area that had been the Bread Basket of the country, and had exported much of their goods to Great Britain during WWI. These letters I catalogued to the file level description, and included detailed Scope and Contents sections, which included where the letter was sent from, the dates that are included, and the general events that Rackstraw writes about. (For more information about the efforts in Russia, the last series includes many lantern slides used to encourage those in London to aid in the efforts, and include graphic images of starving children and adults, between slides of text describing how and why it is Great Britain’s DUTY to assist in this aid.) In 1924 she worked at the Headquarters of the League of Nations, and from 1924 until 1937 was Warden of Masson Hall, Edinburgh University. During this time too she was Adviser of Women Students, Edinburgh University. Documents relating to this period of time are the largest in the collection, taking up one box. It is clear that in those short 9 years she lead and advised the students of Masson Hall, she left an indelible legacy behind her. Though she bought a house in Hampstead following her resignation from Edinburgh University, she remained quite involved with the Masson Hall Association, and in correspondence with previous students late into her life.

often stronger impressions. She spent a year in Paris, France before University, and the collection contains many letters from her mother and father back in England during that time. Her father was a successful businessman, owning several department stores. She attended Birmingham University, where she stayed in University House, a hostel for female students of the University. Here she met Margery Fry and Rose Sidgwick, who were to be sincere friends of hers, and prominent figures in her collection. Though both wardens of the University House, and a good deal older than Marjorie Rackstraw, they shared political interests, and it is easy to assume from their letters that Marjorie gained a passion for volunteer work abroad from Margery Fry. After University, she worked at Moray House at the University of Edinburgh as a Warden spent a year at Bryn Mawr University in Pennsylvania, USA, before taking an appointment in Buzuluk, Russia during the Great Famine of 1921-1923. She worked for a government administration tasked with distributing rations to starving people, and the collection includes over 30 detailed letters and reports she sent her family and Margery Fry during this period. I made the time to read these letters in detail, and it offered a useful perspective to view the rest of her collection, and where her passion for relief started. Most letters are, first and foremost, heartbreaking at their core. Rackstraw presents the facts, her observations, but even from the level headed writing of this down to earth woman, there is no escaping that she watched 1/3 of her village die from lack of food between 1921 and 1922. The springtime was always joyful, and the winters exceedingly difficult. Every accomplishment was met with a complication from the weather, which prevented new plans from going through. This was an effort of survival against the elements, in an area that had been the Bread Basket of the country, and had exported much of their goods to Great Britain during WWI. These letters I catalogued to the file level description, and included detailed Scope and Contents sections, which included where the letter was sent from, the dates that are included, and the general events that Rackstraw writes about. (For more information about the efforts in Russia, the last series includes many lantern slides used to encourage those in London to aid in the efforts, and include graphic images of starving children and adults, between slides of text describing how and why it is Great Britain’s DUTY to assist in this aid.) In 1924 she worked at the Headquarters of the League of Nations, and from 1924 until 1937 was Warden of Masson Hall, Edinburgh University. During this time too she was Adviser of Women Students, Edinburgh University. Documents relating to this period of time are the largest in the collection, taking up one box. It is clear that in those short 9 years she lead and advised the students of Masson Hall, she left an indelible legacy behind her. Though she bought a house in Hampstead following her resignation from Edinburgh University, she remained quite involved with the Masson Hall Association, and in correspondence with previous students late into her life.

From 1937, Rackstraw was in London doing social work and in 1939 was involved in the evacuation of day nurseries and nursery schools for London City Council (LCC). In 1940 she did relief work for refugees in France until the fall of France in June 1940, and there

are letters in the collection from students thanking her for her work. She then did emergency war work, and in 1944, at age 56, she joined the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration in Germany. There she worked with refugees (named Displaced Persons) at Greven, community feeding, and the welfare of old people, including the setting up of hostels. In 1945, Rackstraw was elected Labour Councillor for Hampstead and from 1945 until her death she set up and worked with the Hampstead Old Peoples’ Housing Trust. Rackstraw was Chair of the Hampstead Committee of the Lord Mayor’s National Air Raid Distress Fund, Chair of the Standing Committee on Communal Feeding, Governor of St. Olave’s and St. Saviour’s School, and Honorary President of Niddrie School Association. She was awarded the OBE in the New Years Honours List, 1961. Marjorie Rackstraw OBE died in her sleep on 28 April 1981.

Her collection arrived to the Edinburgh University Archive in 1995 in a suitcase packed by the caretaker of her estate. This caretaker left helpful notes in an untidy scrawl throughout the collection (even the Enigma Machine would have struggled with this puzzle, I think!), but largely I imagine the contents of this collection to have just come from Marjorie Rackstraw’s study; these boxes are full of books, letters, and documents, all filed in well-used manila folders, and labeled in her handwriting the timeframe they took place. So often I imagined what it would be like to sit down with this incredible figure and pull out each letter and ask her how she knew that person, or why she chose to keep this letter for so long. There was only one envelope in the collection that I couldn’t find a single connection to Marjorie Rackstraw, but otherwise with the context of her life, I could make sense of the documents I came across. The biggest theme of this collection that fascinated me most is the relationship between Margery Fry, Marjorie Rackstraw, and Rose Sidgwick. Margery Fry and Rose Sidgwick both became well-known figures of their time; Rose, a medieval history lecturer at Birmingham University, from a well-known academic family, with ties to Oxford, and Cambridge, and Margery Fry, an outspoken and well-spoken penal reformer with deep ties to Quaker relief efforts. These women never married, and openly put their academic, political, and relief efforts at the forefront of their lives, at a time when single women were expected to stay at home and look after their parents. One glaring piece of evidence to this was in Marjorie Rackstraw’s permission to enter France in 1940, which states her occupation as “Spinster”. Continually, I was struck by the bravery and passion these women had to push the boundaries of the gender norms of the time.

My time at the CRC at Edinburgh University was full to the brim of revelations as I put this puzzle of a life together from the contents of four boxes. But what a full life I’ve found! I hope that many researchers gain from the information I’ve organised, and that it provides more clarity to other collections.

What an amazing person, and such an interesting life!

LikeLike

Since then I’ve started working for a private school in Edinburgh, and her name crops up there too!

LikeLike